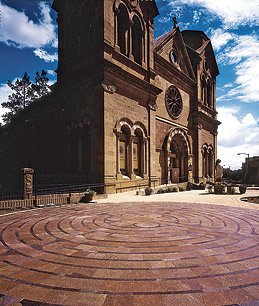

Porphry works in places like St. Francis Cathedral in Santa Fe, NM

In 1992, Renzo Stenico and his son Fulvio located a porphyry quarry in the unlikely village of San Juan de los Rangeles, in central Mexico. It was no accident. More than two decades earlier, the elder Stenico had founded Mondial Porfidi in Trentino, a region in northern Italy that is porphyry's home ground. He'd also learned that the stones had been sighted a continent away. The Stenico family secured extraction rights to a local quarry and created Mexico Porphyry & Stones. "Mexicans call this porphyry 'pigeon's blood' because of the red-and-purple color," says Carlos Gamba, who manages the San Juan quarry.

It's not that the Italians had found an El Dorado in Mexico. But the discovery changed the scale and scope of the porphyry business, which has been dominated by family-owned Italian companies. From ancient times, porphyry — a multitonal crystalline stone formed by the rapid cooling of lava — has touched the lives of royalty, adorning both birthing rooms and tombs. Napoleon's outermost coffin is made of the stuff. Now, more than 2,000 years after porphyry was first quarried in Italy, the stone's commercial appeal as a paving material in the construction of public spaces and residential patios is growing, especially in the U.S. Its new popularity has also put it on the global radar.

When porphyry with a distinctive color is discovered outside Italy — Trentino's 100 or so quarries tend to yield a multitonal gray, reddish purple and rust palette — sometimes the opportunity to toy with geographic tradition is just too good to pass up. That's especially the case when the prospect of cheaper labor comes into play, says Andrea Angheben, technical consultant at ESPO, the region's porphyry-promoting and educational organization, which has a membership of more than 80 companies.

In Trentino, extraction of the stone accounts for annual revenue of about $534 million, says Angheben. More than half the 1.5 million — ton output stays in Italy; 30% is sold to France and Germany. Farther afield, Saudi Arabia and Dubai are recent customers, and some Italian companies are in discussion with Qatar. "They see it's a good stone, and they have the money to buy it," says Angheben, speaking of "certified Trentino porphyry," whose brand is associated with specific production controls. But the Italian stones are no longer the only rocks in town.

In addition to Mexico, Argentina and Australia have joined the fray. About 70% of the Mexican output is sold internally, and 20% is shipped to Italy. Miles Chaffee — owner and CEO of Milestone Imports, in Santa Fe, N.M., and the exclusive distributor of Mexico Porphyry in the U.S. and Canada — takes the rest.

Porphyry has made Chaffee an exporter too. He's sold Mexican porphyry to Japan, Taiwan and even Disneyland in Hong Kong. Increasingly, though, the stones are finding a home in the U.S. as pavers for municipal parks, hotels and universities. In 2008, Stanford University used the stone for the first time to pave a heavily trafficked bicycle and pedestrian area at the center of campus. "The color, which had a purple tinge, sold us," says Kelly Rohlfs, a civil engineer at Stanford who managed the project — and ordered more. The cost, "a lot cheaper than Italian porphyry," was also a factor. High-end residential projects figure into Chaffee's mix too. A 5,000-sq.-ft. (465 sq m) porphyry driveway carries a preinstallation price of about $35,000. Although Chaffee felt the recessionary blow to his bottom line in 2009, this year he expects to move 4,500 tons to earn revenue in the low seven figures.

For Andrea Tomaselli, a porphyry importer and co-owner of Italian Porphyry, in Melbourne, every public-space project he executes advertises the material. In addition to using tiles from Trentino (he's a native)and Mexico, he imports grayish-mauve product from Patagonia. Over the past year, fueled by public-works projects, his business grew 150%. Because design patterns often depend on juxtaposing tiles according to hue and size, he says, "the colors you want determine the quarries you pursue."

Tomaselli now helps run a 15-acre (6 hectare), newly operational quarry of red-streaked blue-gray porphyry on Aboriginal land in Dimbulah, Australia, a lower-cost alternative to the imported stones. The more that porphyry is used and seen in projects, the more demand there is for it, he says, noting that this awareness also helps Trentino sell more of its product. His sales pitch is that with proper care, porphyry, unlike concrete, can last forever. Just ask Napoleon.